Shopping Cart

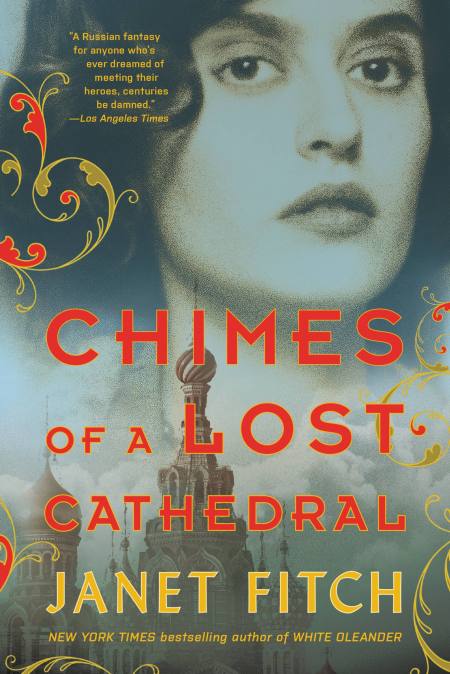

Description

What's Inside

We'll meet again in Petersburg,

As if we had buried the sun there,

And for the first time we will utter

The blessed, senseless word…

—Osip Mandelstam,

"We'll Meet Again in Petersburg,"

November 1920

Part I

Iskra, the Spark

(March 1919–September 1919)

1 Tikhvin

I WAS RISEN, risen from the dead. I had escaped the house of snow and lies, I had been spared.

An icy fog obscured the road the day I left Novinka on the back of the old man's sledge piled with logs, heading for the market town Tikhvin. The countryside revealed itself in the foggy gaps, opening and closing like curtains. The load shifted dangerously underneath me, wooden runners jolting in the ruts. The old man smoked his pipe while I made plans that blew away like snowflakes, into the drifts and gone.

Five days we rode, stopping in villages, sleeping in straw, the child alive and moving within me. It was stubborn, like its mama. My celestial egg. Gathering strength for the jailbreak.

And out rushed oceans

Himalayas

Krakatoas,

warring nations…

Rocketing red and fiery across the dazzled brow

of Nothingness

Till Nothing itself became a memory.

At last, we descended into Tikhvin, a crossroads for centuries, with its river and its railroad, the point of arrival and departure where I'd last left my one and faithless love. His tears had run, but I had not been moved. That vain girl, walking around with her eyes shut tight, thinking that life should be straight and good, that she could pick and choose, like plucking stones out of a handful of rice. But now I was five months along with his child unborn, and had learned that imperfection was part of the weave of the world. I would return to him if I could, and pick up the stitch I had dropped.

Tikhvin was a substantial town of some twenty thousand souls—a number I once thought negligible. Now it was dizzying. So many streets, people, houses, fences, and carts…The giant Uspensky Monastery loomed with its five-towered carillon, its ancient fortress walls, which had once protected the entire population from Swedish invaders. Now Russian soldiers held the town in their grip, hanging about on street corners in their greatcoats, with their rifles and grisly bayonets. A gang of recruits marched toward a barracks, accompanied by shouts and curses. This was the current reality, the sound of the year 1919, the crash and clang of war. Time was bringing me into its brazen dance, leading me by the hand.

After days of nothing more urgent than snowbound forest and the bony rump of the horse, Tikhvin's sprawl and energy unnerved me, and the child recoiled inside me. Like a country simpleton, I marveled at every small sight—the town seemed a metropolis, a terrifying wonder. Every sound amplified, every movement a jolt. I flinched at a carter banging crates to the ground, startled at a shout from a doorway. Now I understood the peasant's terror when he encountered mighty Petersburg for the first time—the din of Nikolaevsky station, the bustle on Nevsky Prospect.

As the sledge scraped along toward the station, I couldn't help but read the signs and portents. I hadn't spent months at Ionia, trapping and hunting, without learning to read the news in sticks and hairs and tracks in snow. All the signs were bad. I saw it in the lean, blue-tinged faces of the arrivals struggling up from the station. Two sallow, soot-eyed women in black coats and too-thin shoes dragged a heavy suitcase between them, loaded no doubt with silverware and bric-a-brac to trade with the peasants for food. He who trades on the free market trades on the freedom of the people. A grim-jawed, silent group of workers following them had to be a food-requisitioning brigade. They neither spoke nor joked—they knew their assignment: to relieve peasants of their grain without recompense so they could feed their own starving brothers. I could see them pulling into themselves, hardening for the job ahead. A number of workers traveling alone walked up the main road, collars raised, a self-provisioning holiday. Their faces told me everything. No food in the city, no help, no end in sight.

Behold, the station. The old man helped me down from my throne of logs, the horse snorted its clouds into the white air. The days of hard travel had taken their toll on my body, I moved like a woman of eighty. Pine pitch and splinters stuck to my sheepskin and squirrelskin gloves. I held on to my snowshoes and game bag, unable to adjust to the assault of so many people. Travelers pushed past me as if I were a turnstile.

I gazed up at the arches. Here was where I went wrong. Here was my chance to begin again.

I shoved my way through the station and out onto the platform, where a train stood steaming, stinking, its wheels terrifyingly outsized. After the timeless introversion of the countryside, the noise scoured my ears, the child's jerking alarm took my breath, and I clutched my snowshoes to my breast. First- and second-class passengers paced the platform, stretching their legs and doing furtive business with the peasant women selling piroshky and roasted sunflower seeds, while third-class travelers huddled in the barn doors of the boxcars, not daring to leave the train, their wooden bunks rayed behind them like shelves in a poor shop. Everyone heading east, east, east, away from Petrograd, into the snowy countryside, toward the Urals, escaping the turmoil and starvation in the capital of Once-Had-Been. My determination wavered. It slipped, shattering against the train's iron wheels.

Perhaps the boy I'd been—Misha, that cheeky lad—would have chanced it. He had his way of staying afloat, but I couldn't conjure him now, not with the child on the way, my face gone round, my breasts past binding. I was a woman in full and there was no escaping it.

Wisdom does not consist of making the best choice among many. Wisdom is understanding when there is no choice and taking the step that must be taken, without complaints or sighs. Hoisting my small bag higher over my shoulder, I walked to the platform's end and climbed down, strapped myself into my snowshoes, and followed the rails through the fog.

A switchman's shack emerged from the milky white. I knocked at the poorly made door, the pearly gates of this sooty heaven, and swung it open without waiting for an invitation.

Inside, a blackened stove warmed the small hut—no better than a wooden crate—where four men seated on boxes played cards. The kettle boiled. Steam coated the one greasy window. But which was the switchman, the one in charge? Him, I decided—the bald one in spectacles, pencil behind ear. The other three, railwaymen: a pensioner—a little bantam cock—and two burly men, one missing an arm, his coat sleeve pinned up neatly. Firemen or mechanics, I thought, the one-armed man wounded in the line of duty, and still drawing rations. Oh, to be the boy Misha again! Misha would know how to talk to them. He would swear, tell a dirty joke. Eh, brothers! But trapped in this irrevocable female form, I had to appeal to mercy, if I could find it. I hated negotiating from weakness, but I could do it if I had to.

"Comrades. Forgive me." I spoke quickly, holding my hands in the universal language of wheedling. "I don't want to trouble you, but I don't know where else to turn. My brother was a Vikzhel man, an assistant engineer. He said if I ever needed help, to turn to the railwaymen." I rummaged in the sack and pulled out Misha's papers, presented them to the switchman. "I lost my position, a cook in a boarding house. The woman's daughter came home from Petrograd and took my place."

The bald man peered at Misha's documents. "Assistant engineer? It says he was fifteen years old." He tried to hand them back to me but I shrank away. My fictional brother was Vikzhel, a union man. They took care of their own.

"He was a good boy." I had no problem staining my face with tears. Poor Misha! "He gave me his pay. It kept us going. But he died, four weeks ago. Now I have nothing."

The switchman held the papers awkwardly, he didn't know what to do with them if I wouldn't take them back. "So what do you want from us, little comrade? We can't put you on as a fireman."

The others chuckled. Oh, so funny. How I hated men who thought what a woman did was ridiculous, what a woman needed. I wished I could pull the gun from my pocket, show him who was ridiculous. But I had to bite my tongue. "I can shovel snow, keep the tracks clean," I said, pushing on. "Cook, wash. Read. Look, I'm not asking for charity." I drew myself up to my full height, trying to appear healthy and robust, not like a pregnant girl who'd been breathing her last calories through her metaphysical skin. "I can water trains. Clean the station." That made them laugh—you were more likely to see a pig fly than a clean vokzal in Russia.