Shopping Cart

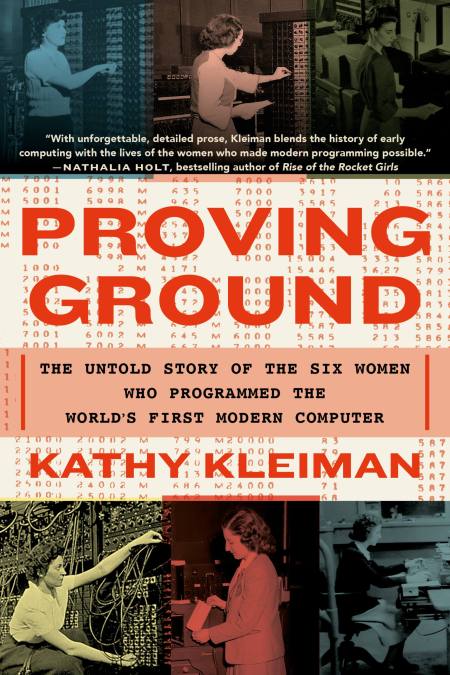

Proving Ground

The Untold Story of the Six Women Who Programmed the World’s First Modern Computer

Description

After the end of World War II, the race for technological supremacy sped on. Top-secret research into ballistics and computing, begun during the war to aid those on the front lines, continued across the United States as engineers and programmers rushed to complete their confidential assignments. Among them were six pioneering women, tasked with figuring out how to program the world's first general-purpose, programmable, all-electronic computer—better known as the ENIAC—even though there were no instruction codes or programming languages in existence. While most students of computer history are aware of this innovative machine, the great contributions of the women who programmed it were never told—until now.

Over the course of a decade, Kathy Kleiman met with four of the original six ENIAC Programmers and recorded extensive interviews with the women about their work. Proving Ground restores these women to their rightful place as technological revolutionaries. As the tech world continues to struggle with gender imbalance and its far-reaching consequences, the story of the ENIAC Programmers' groundbreaking work is more urgently necessary than ever before, and Proving Ground is the celebration they deserve.

What's Inside

Preface

As I stared at the women in the black-and-white photograph, it seemed as though they were trying to tell me something. I was sitting in Harvard’s Lamont Library, a main library for undergraduates, trying to research a paper on American women in the twentieth century who were leaders in computing. I knew of only one, Captain Grace Hopper of the US Navy, later Rear Admiral Hopper. Of course, there was Lady Ada Lovelace, daughter of British poet Lord Byron, who worked on early programming concepts in the nineteenth century, but she was out of scope for an American women’s history course.

I was a young woman in computing, and I wanted to know if there were others. I had taken computer science since I started college, and while my early programming courses were composed of about half women, my latest class had only one or two. I knew I would feel more comfortable in computing if I saw a few more women in class with me, and this drove my interest in who came before me and what they had done.

Open before me, spread across the reading room table, were encyclopedias of computer science and histories of computing. Notice- ably absent in all of them were the names of women, except Ada and Grace. But noticeably absent, too, was any real history of programming. The stories were all about hardware and the men who built the mainframe computers that dominated computer history in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s.

But what about those who pioneered ways to communicate with the large computers? Instruction codes and programming languages also date back to the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, but where were the stories of the people who wrote them?

Then I stumbled on a black-and-white photograph of a huge, black, metal computer dominating three sides of a large room and dwarfing six people—four men and two women.

There were two men in the middle of the photo, two women on the right with a man in uniform between them, and a man in the back left. Only the two men in the middle were named—J. Presper Eckert and Dr. John Mauchly, co-inventors of ENIAC, the world’s first all-electronic, programmable, general-purpose computer. It was built at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) during World War II. Nowhere in the captions or accompanying article were the other people in the photograph named.

I studied the image closely, especially the women. They were young, with World War II–era hairdos, flat shoes, and skirt suits. As I leaned in closer, what struck me was that they seemed to know something about ENIAC. They appeared to be comfortable, knowledgeable as they adjusted knobs on and read documents next to this vast, seemingly living and breathing giant. I could not stop looking at them.

I knew something about computers. My father was an electrical engineer who specialized in new technologies. He brought home electronics for us, including an early calculator, clunky and huge compared to today’s versions, with only a few functions, but fascinating and fun to play with. He was the first person I knew to talk about speech synthesis and voice recognition. My father had written his dissertation on the founding of the semiconductor industry and was certain that the miniaturization of electronics would continue and would keep changing the world.

Friends asked me in junior high school if I wanted to learn to pro-gram computers, and I said yes. So I joined an Explorer Post, a coed branch of the Boy Scouts dedicated to career exploration, and went off to spend my Wednesday nights at Western Electric, a manufacturing arm of AT&T near my home in Columbus, Ohio. I learned BASIC, a programming language invented at Dartmouth in the 1960s. Soon I was playing games my friends wrote and adding one of my own, a version of Mad Libs that I wrote in BASIC. The first time my friends played it and laughed out loud at the funny story the computer printed, I knew I was hooked on programming.

Looking at the old black-and-white picture, and the men and women standing before ENIAC, I longed to know more about their story. I dug deeper, found more books, and uncovered another photo- graph. This one was a close-up showing two young women standing right in front of ENIAC. Once again, no names of the women, only the name of the computer.

I made copies of both pictures and took them to my professor. Anthony Oettinger was a former president of the Association for Computing Machinery, an international group for computing professionals.

I showed him the two ENIAC photographs. “Who are the women?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Professor Oettinger answered, “but I know who might.”

He told me to visit Dr. Gwen Bell, cofounder of the Computer Museum, then in Boston and now in Silicon Valley.

The Computer Museum was at the far end of Museum Wharf in downtown Boston. As I walked down the long wharf, I noticed the Children’s Museum and in the water, the Boston Tea Party ships. All great to visit, but I was on a different mission as I clutched my folder of photographs and disappeared into the Computer Museum.

I found my way to the office of the museum’s director. Bell was in her early fifties with short, dark, graying hair, clearly a no-nonsense, busy per- son. I opened my folder and once again found myself pointing to the black-and-white images of the women who were standing in front of ENIAC.

“Who are the women?” I asked Bell.

Unlike Professor Oettinger, she knew. “They’re refrigerator ladies,” she said.

“What’s a refrigerator lady?” I asked, baffled as to what she was talking about.

“They’re models,” she responded, rolling her eyes. Like the Frigidaire models of the 1950s, who opened the doors of the new refrigerators with a flourish in black-and-white TV commercials, these women were just posed in front of ENIAC to make it look good. At least that’s what Dr. Bell thought.

She closed my folder and handed it back to me. I was dismissed.

I slowly headed out of the museum. I saw the children lined up on the wharf getting ready to enter the Children’s Museum, the Bos- ton Tea Party ships rocking in the harbor, and the bright blue sky. But Bell’s story did not make sense to me. I had stood in front of big computers before. The first time you see them, they seem huge, over-whelming, almost surreal. The young women in the ENIAC pictures looked confident and assured. They looked like they knew exactly what this huge computer did and why they were in the photos. They did appear posed, but so did the men, and the men were not models.

As I left the wharf, I set a task for myself. I was going to find out the names of the women. I would learn what they had done in order to be in these beautiful, black-and-white pictures of ENIAC in the 1940s.

I was going to learn their story.