Shopping Cart

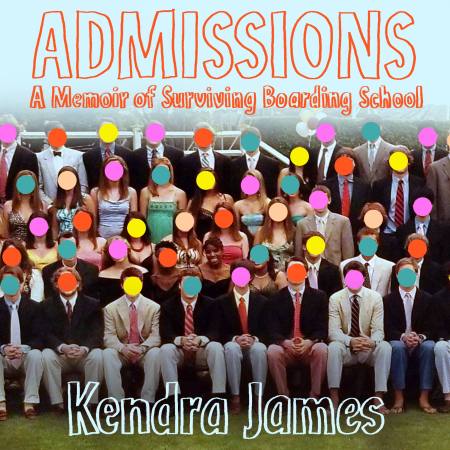

Admissions

A Memoir of Surviving Boarding School

Description

Early on in Kendra James’ professional life, she began to feel like she was selling a lie. As an admissions officer specializing in diversity recruitment for independent prep schools, she persuaded students and families to embark on the same perilous journey she herself had made—to attend cutthroat and largely white schools similar to The Taft School, where she had been the first African-American legacy student only a few years earlier. Her new job forced her to reflect on her own elite education experience, and to realize how disillusioned she had become with America’s inequitable system.

In ADMISSIONS, Kendra looks back at the three years she spent at Taft, chronicling clashes with her lily-white roommate, how she had to unlearn the respectability politics she’d been raised with, and the fall-out from a horrifying article in the student newspaper that accused Black and Latinx students of being responsible for segregation of campus. Through these stories, some troubling, others hilarious, she deconstructs the lies and half-truths she herself would later tell as an admissions professional, in addition to the myths about boarding schools perpetuated by popular culture.

With its combination of incisive social critique and uproarious depictions of elite nonsense, ADMISSIONS will resonate with anyone who has ever been The Only One in a room, dealt with racial microaggressions, or even just suffered from an extreme case of homesickness.

Praise

What's Inside

PROLOGUE

For three years after graduating college, my Saturday morning routine was set in stone. Instead of sleeping in, I would get up with a 7 a.m. alarm. I pulled on a pair of Kate Spade heels, squeezed into something professional and high-end-looking from my favorite floor at Lord & Taylor, and took the 6 train down to my designated Saturday morning haunt: a school theatre overflowing with parents on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

Each week from December to June, as many as 250 mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and responsible almost-adult play-cousins of middle schoolers made their way to one of New York City’s most prestigious and expensive schools by 9 a.m. They arrived to vie for admission to the Scholars Striving 4 Success (S34) program, which—after months of grueling extra academic work—would guarantee their child a spot in an independent school in New York City or a boarding school in New England. Schools built atop precise, sharp-sounding consonants, with single-name recognition, like Spence, Choate, Hackley, Exeter, or Collegiate.

Our program only accepted children of color, and this early in the morning they visibly slumped in their seats.

Their parents’ eyes, on the other hand, grew wider with hope the longer the meeting went on. Some only brought their single young applicant, but many came with two or three children, because the child old enough to watch their younger siblings was the one old enough for our program.

They came to listen to us—all independent school admissions professionals—make them an offer that was a foreign concept to many, in a language that they might not even understand. There were never less than three distinct dialects spoken in that room at once: My Dominican boss would tackle the Spanish speakers, and I would torture Haitian parents with my very basic grasp of high school French and the patois I’d picked up from the bodega clerks and stoop sitters in my Harlem neighborhood, coupled with what was essentially a four-year-old’s pronunciation. Thanks to a few high school and college friends, I could greet Korean speakers respectfully before staring blankly at the stream of language that followed. God help you if you spoke Bengali, or any other language that some Nick Jr. cartoon hadn’t capitalized on yet. Those families relied on their children to do most of the translating. But they still came. Their commitment was palpable, and understandable.

We were selling what essentially amounted to seventy Get Out of Jail Free cards; one of the few golden tickets out of the New York City public school system, a ticket that most in the room believed to be the first step toward a better life for their kids. Even if their child was excelling in their current school, and even if that school was a good one, they believed that we would be able to give them something better. And instead of giving them insights on how to make the most of the public school system or working for an organization that would help improve it, our program opted for surgical student extraction. In our hands, the idea of the American Dream was both a temptress and a cudgel. The schools we offered to their children in turn gifted them access to the highest echelon of society—the status that everyone outside of the wealthy 1 percent has been told they can bootstrap their way into through the bill of goods that comes with the American Dream. I peddled the illusion of ownership, delusions of grandeur, myths of American upward mobility, and the misconception that there is, indeed, a place where everyone can feel like they belong.

Everyone in the room was low income by some definition, whether they were truly surviving below the poverty line, or they existed within that warped sense of “broke” that comes with living in New York City for too long. The “New York Poor” peppered the auditorium each week alongside those who lived paycheck to paycheck or on none at all; people who were making over $250,000 a year, had no debt, and had only one kid, but because they couldn’t keep up with their neighbors and didn’t have an in-unit washer/dryer, they went around telling everyone they lived in abject squalor. This wasn’t a meeting for those people, but it didn’t stop them from trying. Everyone wants to give their child a leg up, and an upper-middle-class Black child often needs just as much of one as their white peer whose family receives government aid.

We weren’t selling meeting attendees on the idea of being rich or New York Poor, but wealthy. Privileged. Well-rounded and well-off. Their children would finally be on a level playing field with the children of executives, movie stars, politicians, and Mike-down-the-street—that one inexplicably well-off neighbor whose great-great-great-grandfather happened to have grabbed a homestead and enslaved three people in Missouri at some especially opportune time in 1843 and they’ve just been wealthy ever since, because America.

“Your kid could be one of them! Well situated! Connected for life! Achieving the American promise that a child will always have the opportunity for an even better life than those who came before them,” we told hopeful parents, once their children had been herded into another room to take the ridiculously outdated test they needed to pass in order to be considered for our program. Being granted access to upward mobility required, in this case, being able to neatly fill in a Scantron sheet, sit still during a three-hour exam, and solve math problems in a booklet copied via a machine that was just as likely to make a + look like a –.

In my nicest clothes, sometimes with the addition of my bright- est string of pearls, I would stand in front of them looking every part the perfect graduate of a New England prep school. I smiled at them as I spoke, completing a package that said: This is what your child could look like in ten years. This is what a Black woman with an independent school education and a college degree looks like. This is what she does on her Saturday mornings. This is the pleasing, unaccented American voice they’ll learn. This is the kind of job they’ll have.

I gave the same practiced speech every week.

So, here’s the story I always start off with when I’m trying to explain why an independent school was right for me. The year before I transferred out to Taft, I did my freshman year at a public high school in New Jersey. I barely made it through the freshman Algebra 1 course; it was making me and my teacher miserable. Same with freshman-level biology!

Flash-forward to my sophomore year at Taft. I find out: Not only was I terrible at Algebra 1, but the Algebra 1 course at my public school was behind the same course at Taft. I still had to take it again just to catch up. It was just this constant struggle, once again, between me and my teacher. We both wanted me to get it, but it was quickly becoming apparent that I just wouldn’t.

But that’s what’s so great about independent schools, right? They’re not beholden to state education requirements—that means no arbitrarily required classes, no mandated math and science minimums, and no standardized state exams on those subjects. So, because I was in a boarding school, there came a point where we could just all sit down and say, “Hey. This isn’t working out. Let’s try something else.”

In my case “something else” meant opting out of math classes after I’d done the bare minimum and putting me in more humanities classes. I never made it to physics in high school, but I took screenwriting and adolescent psychology. I can’t balance an equation, but I can hang lights in a theatre and run a sound board. I began to figure out what it meant to really reflect in essays on my behaviors and personal interests, which has led to a fruitful writing career. I bet some of you out there have kids who think they’re the next LeBron James or a budding CC Sabathia too, right? I never took statistics, but one Wednesday after lunch I finally landed my double salchow, because I could use one of my school’s two full-sized ice rinks whenever I wanted.

What would “something else” mean for your child? Think about all the ways an independent school might allow them to follow their own paths and succeed in ways that their current schools won’t.

This isn’t to say that your child won’t be challenged. They will be. The standards at each of the schools we work with are incredibly high, and your child will be asked to meet goals that might seem out of reach now, at age ten. But these schools set the bar high so that your child can walk down the aisle after graduation knowing that the whole world is at their feet. Have you looked around this beautiful theatre? Did you take in the quality of classrooms while you were walking the halls? It’s a short leap from a school like this one to a college like Columbia, Yale . . . or Harvard.

(Here, I always paused for the approving murmurs that simply hinting at the name “Harvard” brings out in a room full of parents.)

I know that this might feel like a very different environment for some of you and maybe you’re worried that schools like this one might be isolating for your children. It is an adjustment! But it’s a short one, and it’s worth it. What you have to understand is that schools like this one want us there— Black, Latinx, Asian . . . everyone here. They’re excited to have us, and your kids won’t be treated any differently for who they are or how much money you make as their parents. These schools are for everyone.

One of the huge benefits of an independent school is the class sizes. For instance, I graduated in a class of just under one hundred students. By the time they’re ready to graduate, your kid’s teachers will know your child like the back of their own hand, and that means when it comes to college recommendation letters or references for summer internships you couldn’t ask for a better resource. You won’t find anyone more ready or willing to advocate for your child than a teacher at an independent school.

And the other benefits? When you’re in a class size that small, kids make so many friends, ones that will last for life and ones that will only benefit them later on as they’re starting out professionally. Imagine going to school with Michael Bloomberg’s kids! Your children will be in classrooms with the daughters of politicians, actors, bankers, and executives, and they’re going to learn how to use those connections for their own advantage. For your advantage, even.

I’m still excited every time I go back to Taft. It’s a place I know I’m always welcome. I can walk onto the campus whenever I want and visit old teachers and friends and say hello and just soak in all the good memories of the place. My name is engraved into a brick on the ground there, along with the rest of my graduating class, and all the graduating classes before ours. It makes it feels like all of us—every student—owns a bit of the place. Taft was the first place that ever gave me a feeling of ownership about my surroundings, and I think that’s so important when you’re growing up a person of color in America.

I want that same feeling for your kids as well.

As an admissions counselor at Scholars Striving 4 Success I sold a lie for a living; at least, that’s what it felt like. With my fake smile, pearls, and the rose-colored glasses I’d become accustomed to tinting my own time at Taft with, I lied to a roomful of people every time the word “racism” failed to arise in my speech. Every time the phrase “The Black Table in the dining hall” didn’t come up. Every time I didn’t mention the word “legacy.” Every time I didn’t let myself taste the bile I can still conjure to this day if I think too long and too hard of the name Emma Hunter.

Each year at Scholars Striving 4 Success we filled every one of the seventy slots in our program. Each year our waiting list grew ripe on its summer vine. We were very good at our jobs. I was one of the best.