Shopping Cart

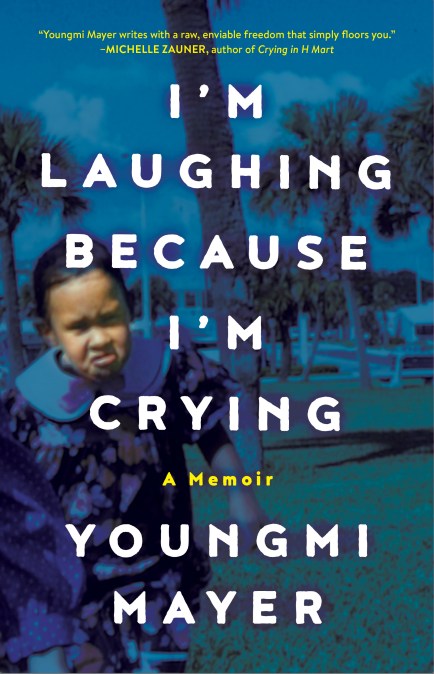

I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying

A Memoir

Description

Elle‘s Best Nonfiction Books of 2024 | The Boston Globe‘s Best Books of 2024 | San Francisco Chronicle‘s Best New Books of Fall 2024

From standup comedian Youngmi Mayer, an unforgettable memoir written with “raw, enviable freedom that simply floors you,” interrogating whiteness, gender, and sexuality in America, navigating a tumultuous childhood in Korea and Saipan, and coming to terms with her parents’ shortcomings (Michelle Zauner).

“Do you know what happens if you laugh while crying? Hair grows out of your butthole.” It was a constant truism Youngmi Mayer’s mother would say threateningly after she would make her daughter laugh while crying. Her mother used it to cheer her up in moments when she could tell Youngmi was overtaken with grief. The humorous saying would never fail to lighten the mood, causing both daughter and mother to laugh and cry at the same time. Her mother had learned this trick from her mother, and her mother had learned this from her mother before her: it had also helped an endless string of her family laugh through suffering.

In I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying, Youngmi jokes through the retelling of her childhood as an offbeat biracial kid in Saipan, a place next to a place that Americans might know. She jokes through her difficult adolescence where she must parent her own parents: a mother who married her husband because he looked like white Jesus (and the singer of The Bee Gees). And with humor and irreverence and full-throated openness, she jokes even while sharing the story of what her family went through during the last century of colonialism and war in Korea, while reflecting how years later, their wounds affect her in New York City as a single mom, all the while interrogating whiteness, gender, and sexuality.

Youngmi jokes through these stories in hopes of passing onto the reader what her family passed down to her: The gift of laughing while crying. The gift of a hairy butthole. Because throughout it all, the one thing she learned was one cannot exist without the other. And like a yin and yang, this duality is reflected in this whip-smart, heart-wrenching, and disarmingly funny memoir told by a bright new voice with so much heart and wisdom.

“Youngmi Mayer has the incomparable ability to find something funny in the most life shattering material. She writes with a raw, enviable freedom that simply floors you.”

Michelle Zauner, author of Crying in H Mart

What's Inside

PROLOGUE

When I initially had an idea to write a book, I kept thinking why should I write a book? I am a dumbass and a loser and why would anyone read it to begin with? What would the book even be about? Then I realized what if that was what the book was about? The fact that I call myself a dumbass and a loser all the time? After all, it’s what got me here in the first place. It’s the thing that seems to separate me from all the other Asian American comedians. The showing of all my cards. The fact that I am a failure and fucking nuts and also constantly bring it up. Someone online once called me the “mentally ill Ali Wong,” which is weird because I would argue that she already comes off as mentally ill (complimentary). But I think what they meant by that was being mentally ill is sort of my thing. I literally won’t shut up about it. I bring it up every 5 minutes because I can’t rely on actual comedic talent like she can. When I tell a joke, no one laughs and instead of working on my craft, I spiral and post a bunch of my unhinged inner thoughts. People like that because it’s relatable.

It’s not really new for an Asian person to come off as a failure or a weirdo. To subvert the stereotypes that we are all perfect, hardworking, and smart. Literally Ali Wong does that, too. But I think there is a level to my realness that still takes people by surprise. I am comfortable saying shit that I truly should not be saying in any situation. I am not only comfortable with it, it’s where I have found my strength. I realized that I have gained a following because I’m willing to openly admit the things that so many people spend their entire lives trying to cover up. A lot of people find it off-putting, but for others, it’s a respite from an endless existence of shame. They see me displaying openly something they’ve been running away from all their lives and feel relief. I also receive a huge benefit from this relationship with people who relate to my material: it makes me feel like I’m not alone and that I’m not crazy. Well, I am crazy, but so are a bunch of other people.

Another aspect of my work that people seem to enjoy is that I talk about being Asian with an air of confidence that seems to be lacking in other Asian American comedians. I attribute this to being raised in Asia. I am missing the pathological implication that I’m inferior to white people that is injected at the very beginning of the formation of Asian American identities, when they’re born in Wisconsin. I think this deep imprint is almost impossible to erase in Asian Americans raised here. There’s no way for an Asian man to undo the fact that half the time he met someone throughout his years in school, they would make a small penis joke. That sort of psychological terrorism lives in their bodies, It changes the way they stand. The way they walk. Asian women here grew up answering the phone at their mom’s nail salon and heard prank callers scream “Me love you long time!” or “How much for happy ending?” on a daily basis. They hold that in their shoulders. They move the way a caged animal moves. I do not move like that. I do not joke like that. I was allowed to form an idea of myself outside of it. I think Asian Americans sense this, and they are comforted by it and made confident from it. They can trust I will never hurt them for the cheap reward of a white laugh. Or even if I do, I will include something that hurts white people way more at the end.

Speaking of shared Asian American experiences though, there’s nothing I can say about my experience as an Asian American that hasn’t already been said in Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. I thought that was a joke until I re-watched the movie version to write this prologue and then spiraled about how I should just throw the whole book away because everything’s already in that fucking movie! Based on a book written in what, the 80s?? NOOO. But my story isn’t only about all the Asian-y “my mom got thrown into the river” trauma that it shares with The Joy Luck Club. My story isn’t about the parts of my life that are subversive to the Asian stereotypes, like me doing heroin in my 20s or becoming a single mom in my 30s who fucks guys who skateboard. My story isn’t even about me being mentally ill. My story is about the fact that no one else in the world has lived my life.

All Asians Americans probably have pretty similar background stories. But so do all the white guys who were the only ones allowed to write books for the last 27,000 years and lord knows that’s never stopped any of them. Every year, since the invention of papyrus, like 10,000 college professor white guys write a book about how hot 16-year-old girls are. But none of them ever seem to think, “Wait, has someone done this before?” None of them ever seem to think that they’re dumbass losers that maybe need to shut the fuck up. So why would I think that?

***

When I was a kid growing up in Korea, sometimes my classmates and I would walk by the pet store to ogle the puppies. We would all crowd around the window to choose the puppy we would purchase if our parents actually let us have dogs instead of beating our asses every time we asked. We chose the puppies by their personalities. Usually, the other kids would all fight over the friendliest ones, but I always chose the sad pathetic ones with boogers in their eyes because I felt sorry for them. A few other girls would choose the sad pathetic ones, too. Our view of puppy ownership was about caretaking and being sad, not the actual joys of having a puppy. Even in our fantasies, we didn’t let ourselves fly high. We grew up to be the teenagers who chose Joey Fatone as our N’Sync boyfriend.

These dogs were severely inbred “pure breed” dogs: Pugs, Malteses, Yorkshire Terriers. They were bred for physical traits favorable to humans despite the fact that the traits were deformities detrimental to the health and longevity of the dogs themselves. Above all, they were bred to be identical because it was important for a breeder to expect the same thing again and again. But their tiny dog souls rebelled against the fallacy that they were interchangeable objects by having distinct personalities. Like these puppies, Korean girls were expected to be exactly the same. We all had the same hair, same uniform, same bodies and were trained to have the same behavior. We saw ourselves in the puppies: powerless objects created to appease the selfish and confusing desires of cruel adults. Since we were all the same, we could see that each one of us were different, just like each puppy was different. We could tell all of them apart. But the adults could not.

One day after school, my friends and I stopped by the pet store to see the owner pulling a sick puppy out of the window. We saw him carry it to the back and asked him what he was going to do. He said he was going to throw it away because it was dying (Koreans dgaf). We all screamed and cried. He looked confused. His wife ran out of the heated room in the back with a flimsy plastic fly swatter in her hand, slapping us with it while screaming for us to leave. By the time she shoved all of us out of the store, we were sobbing uncontrollably. Some of the girls started wailing like we saw the old people doing at funerals. We walked like this to the playground, where we continued to cry all afternoon long, together. A litter of Korean girls. All the same thing.

I moved to America when I was 20. Part of the reason I moved here was because I no longer wanted to be the same thing. However, upon my arrival, my new Asian friends warned me that white people would not be able to tell me apart from other Asians. I thought it was a joke. Reader, it was not. White people will confuse a 50-year-old Chinese woman with a 25-year-old Filipina woman just because they work on the same floor. White people are confused as to why this offends Asians so much. It’s the same confusion I saw on the face of the pet store owner that day when we started crying because he was throwing the puppy away. Our sadness confused him. He didn’t understand why it mattered if one of the puppies died. There were so many more of them we could play with in the window, and they were all the same thing.

We know what it means when white people can’t tell us apart. It means that they can throw us away.

The reason I have to write this book is because I know a lot of you reading this have bought this lie that we are all the same. Maybe white people taught it to you or maybe it was an old Korean pet shop owner. Maybe that old Korean pet shop owner was your own father. Maybe you were convinced like I was that Amy Tan said everything you ever wanted to say 40 years ago. But even if your name is Waverly and your tiger mom forced you to play chess while growing up in San Francisco’s Chinatown, your story would not be the same story. What I realized was that even the dogs bred to be identical never bought into the lie that they were the same and therefore worthless. It never occurred to those puppies in the window that they didn’t deserve a voice. They barked whenever they wanted to. Those bitches barked all the time. Just like white guys. White guys never fell for the lie either. Every day, a white guy who looks and acts like every other white guy wakes up and thinks, “My god I am unique and everything I say is important and probably has never been said before!” and then starts a podcast. Honestly, that guy is right. Good for him. Unfortunately, he thinks that right is reserved only for him and dogs that look like him. How silly.

Here’s the thing though: we are all the same thing. If you look at a yin yang symbol, at first you think it depicts a binary of white and black, but the symbol isn’t the split down the middle, it’s the circle encompassing both. We aren’t one side or the other, we are both sides, forever and ever. There are two wolves inside of you: a white guy who can’t shut the fuck up and an Asian woman who feels ashamed every time she talks. You are both. They are you and you are them. The White guy and Asian woman live within each and every one of us. For me, this is quite literal since my dad is white and my mom is Asian.

Because of this, all my life I have been forced to split the circle in two and choose which side I am on. Am I white or Korean? Am I rich or poor? Am I fat or skinny? Am I a girl or a boy pretending to be a girl (which is something my Korean classmates always accused me of because I was .5 kilograms heavier than all of them)? I tried to separate the two parts of myself all my life and analyze them to know which side I was supposed to be on. Everything I did I examined to see if it was a White thing or a Korean thing. But I could never figure it out. Slowly it dawned on me that the reason I couldn’t figure it out was because they were both the same thing. White people aren’t really different from Koreans. No one is. None of us are all that different. After being forced to see everything in a binary all my life, I realized the binary isn’t real.

So, here’s my story. Is it going to be like The Joy Luck Club? Yes. Parts of it. There are some references to dragons and yin yang symbols and a lot of Asian mom trauma. There will be many similarities but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t deserve to be said. There will be many differences but that doesn’t mean it is not relatable. To read this book is to avenge the death of the puppy who got thrown away. It’s to understand that if a dumbass loser like me deserves to be centered, then maybe so do you.

I’m crying because I’m laughing.